Artist Lydia Pettit's latest exhibition uses horror tropes to confront PTSD and sexual trauma. Emily Steer looks at the visual artists using grotesque and terrifying images in surprising ways.

Horror films and stories confront us with the darkest parts of life. For the visual artists who use them in their work, horror tropes can provide a route to healing and empowerment. Some subvert culturally entrenched clichés, such as stigmatised female bleeding and demonised witchcraft. For others, the horror of lived experience is conveyed through grotesque imagery.

More like this:

- The man hunting down dead celebrities

- The vampire movie the critics got wrong

- The horror shocker that set off a culture war

"Horror has given me the strength and language to discuss trauma and things I'm ashamed of in a way that distances me from them," says Lydia Pettit. The London-based artist has just opened a solo exhibition, In Your Anger, I See Fear at Berlin's Galerie Judin, in which she inhabits the roles of terrorised victim, knife-wielding killer and formidable witch. She confronts sexual trauma and PTSD through painting, addressing not just the victimised parts of herself, but also her sense of vengeance.

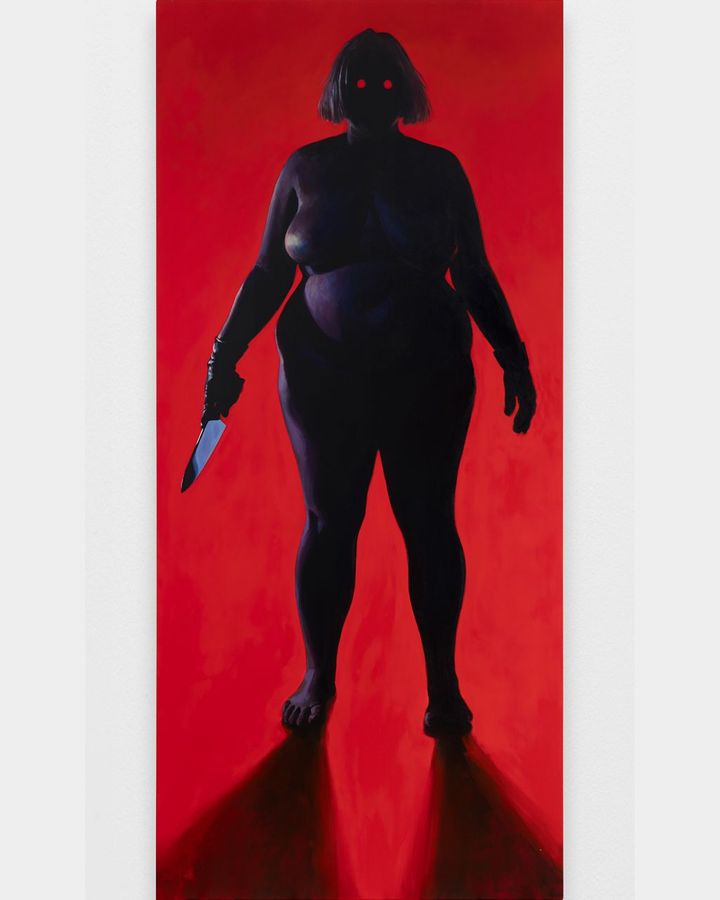

Lydia Pettit, I Am Inevitable (Credit: Elliott Mickleburgh)

"The villain character in my work is about me giving my anger and pain this extremely powerful, monolithic presence so it can live outside my body," she says. "Painting myself as a naked, knife-wielding monster is a way to confront the reality I'm living with; the ramifications of swallowing my trauma and trying to appease people all my life. Putting that entity on canvas and confronting it, while also knowing it's me, is a great way to process and take back control."

Horror can offer a nuanced visualisation of the psyche. Analyst and author Lisa Marchiano co-hosts This Jungian Life podcast, which delves into themes such as beauty and sex through psychoanalysis and storytelling. "Carl Jung talked about 'the shadow', and there are many manifestations of it," she says. "It might be parts of ourselves that aren't allowed, or parts that are evil that we have to contend with. A lot of horror films show us triumphing over evil, which might be an image of the ego contending with these parts of the psyche."

A horror-themed episode of the podcast addresses the role of the monster within such narratives. "There's an incredible song, Weeping, by Dan Heymann," she tells BBC Culture. "It's about this monster that's locked up and intimidated; people come to look at it. When everything goes quiet you realise that the monster isn't roaring, it's weeping. It's about apartheid, where a group of people were othered and made to be the monster. Viewed from a psychological angle, monsters could be seen as parts of ourselves that we've disowned. That part of us is often where our pain is that wants to be known, integrated and loved."

Six contemporary artists share how they embrace or subvert deep-rooted ideas of the monstrous within their work.

Marianna Simnett The Bird Game, 2019 (film still) (Credit: The artist, Société, Berlin, FVU, the Rothschild Foundation, and Frans Hals Museum)

Marianna Simnett

Marianna Simnett reveals the wicked parts of the mind that many experience from childhood but few acknowledge. Her films evoke the "subtle undercurrents that are always simmering beneath the surface of our daily existence," she says. "We're all culpable of enacting violence on others."

Films such as The Bird Game and Confessions of a Crow employ the conventions of twisted children's tales, with paranormal animals and young actors. "I think the problem with our Western conception of children is that they are pure and innocent and don't have any dark feelings." Simnett candidly rejects the constrictive expectation of childhood innocence that gives rise to guilt and shame, and in doing so creates space for all parts of the mind to exist.

Simnett combines uneasy terror with humour, fetish and hybridity. While her works often transport viewers to imagined spaces, they capture the vulnerability that many feel now. "We're living in a very psychologically taxing time where our world is full of major contradictions and paradoxes," she says. "Horror as a genre is able to express the fragility that one feels in one's body when the external world is at the brink of collapse."

Grace Ndiritu, Labour: Birth of a New Museum, 2023, one channel, video - aspect ratio 4:3, stereo sound (film still). (Credit: Courtesy the artist and Kate MacGarry, London)

Grace Ndiritu

While shamanism has long been negatively connected with witchcraft and stereotyped in Western culture, Grace Ndiritu celebrates its potential for healing. "Shamanism has historically been feared because Western thinking sees the world as dead, not animistic," she says. "If you don't believe in anything that can't be scientifically proven or rationally thought about, these things need to be feared. Most indigenous cultures and a large percentage of the non-Western world believe in something that is other. The power of the natural world is particularly important in terms of healing."

Ndiritu has, since 2012, explored the role of shamanic and non-rational methodologies in gallery spaces through her series Healing the Museum. The project is now showing at SMAK in Ghent. Working with performance and inclusive activities, the artist aims to reactivate the sacredness of cultural spaces, and leads groups on healing trauma. "It's taken 20 years for this practice to really be taken seriously," she says. "When I began the project, I felt museums were dying and the only way to heal them was to bring new energies into them."

Jenkin van Zyl, Looners, 2019 (film still) (Credit: Jenkin van Zyl)

Jenkin van Zyl

Working across film and immersive installation, Jenkin van Zyl unites horror, fetish and club culture. His subversive works full of monstrous creatures and narratives of self-destruction contrast with 21st-Century capitalism and its expectations of conformity.

"Horror is exciting because it sees the potential of marginality to be a source of power," he tells BBC Culture. "I often create spaces that relish the idea of collapse, entropy or ruin as potential for countering global politics. In a culture that puts so much violence on non-conforming or gender-queer bodies, I'm interested in creating spaces where unruly bodies not only survive but flourish."

A recent exhibition at Edel Assanti in London saw Van Zyl erect a "love hotel" that housed a looped film, in which rat characters engaged in a relentless dance contest. Cyclical ruination often features in the artist's works, defying the industrial myth of progress. "It's the idea of bodies that can go through trauma or collapse but then also regenerate," he says. "I'm presenting things that may be seen as monstrous and horrific as glamourous and sexy, and things traditionally seen as beautiful as alienated and useless."

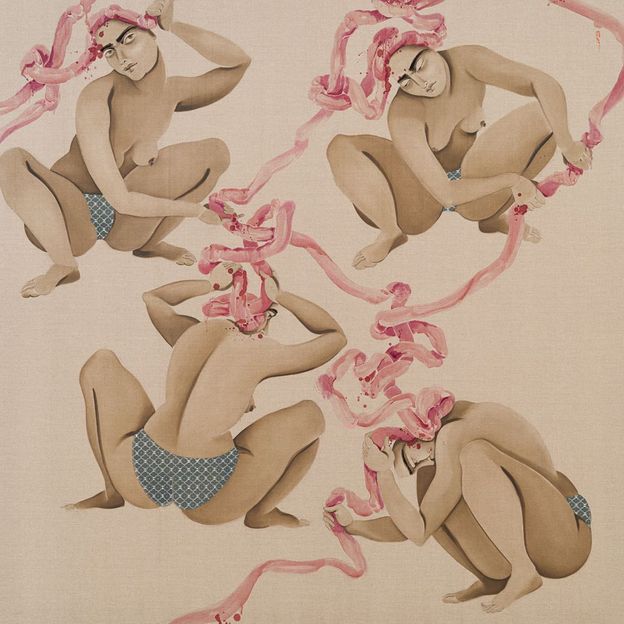

Hayv Kahraman Entanglements with torshi no.2, 2022 Oil and torshi on linen (Credit: Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corria)

Hayv Kahraman

Hayv Kahraman's intricate paintings reclaim the horror of her experience of immigration. She depicts women bent to extreme angles, showing the body as a site of both violence and self-possession. "When one is subjugated, dehumanised and completely robbed of any juridical rights, the body is the last site in which one has autonomy," she says. "The body for me is a site of resistance and re-existence. It's a vehicle to question and rework the various injustices that have plagued it and pinned it down."

While her women assume excruciating poses, they have undeniable strength, sometimes directly watching the viewer who gazes upon their tangled forms. "The 'looking back' is a confrontation… They are saying, 'I know how I'm seen and I'm here to challenge that.' I always think about [WEB] Du Bois's 'double consciousness', where he speaks about the sensation of looking at yourself through the eyes of the other. In this case the other is the dominant white heteronormative society."

In her most visceral works, knotted guts tumble from open mouths and torsos. "As somebody who has felt dehumanised, and lived through the trauma of assimilation, which mostly involves the erasure of oneself, the instinctual or the gut feeling is something that needs to be repaired," she says. "I wanted to reconnect and regain my gut feelings."

Lindsey Mendick, Where The Bodies Are Buried, installation view at YSP, 2023. (Credit: Courtesy the artist. Photo © Jonty Wilde, courtesy YSP)

Lindsey Mendick

Gothic literature inspires Lindsey Mendick, whose ceramic installations visualise intense psychological experiences. Her 2023 shows at the UK's Yorkshire Sculpture Park and Jupiter Artland have been part inspired by gothic tales: Edgar Allan Poe's The Tell-Tale Heart and Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

"I tread towards the gothic because it's hard to describe the horrors of the everyday without it," she says. "We have things ingrained in our culture, like werewolves, that come from deep-rooted fears we have about our place in society. So much of life I find deathly frightening, and I have this abject terror about the simplest of things. When trying to explain it, the idea of horror and being other have been so powerful to me."

Humour and the grotesque both combine in her work to create scenes that feel larger than life, taking the emotions within her work to an overwhelming scale. The limitlessness of horror interests Mendick, providing a space for the mind to run free. "For an artist, horror can be such a wealth of rich material because it shows the depth of the human imagination when left by itself."

Taryn O’Reilly, Glory Guts (Credit: Photos taken and edited by Paulina Fi Garduño and enorê)

Taryn O'Reilly

Taryn O'Reilly, an artist at Lee McQueen's Sarabande foundation, celebrates and reclaims the monstrous feminine in her work. She was drawn to horror through her experiences of PTSD. "The 'final women' who survive horror films experience extreme trauma," she tells me. "They have to become monsters and lose their femininity, lose who they are morally, so they can survive."

O'Reilly is also interested in embracing the motif of blood, which "has always been synonymous with the female body," she says. "There is a fear of women owning those things. It's where the policing of cis women's bodies comes from. Carrie is so relatable. Sometimes you want to be Carrie, at the prom, covered in pig's blood."

Her sculptures feature comically grotesque features: bright pink tongues fill oyster shells; metallic gloves feature talon-like manicures. She is inspired by the clichés of death as a woman through art history: during the plague, death is a monstrous winged woman, inspired by Eve who brought the first sins of men. At the height of syphilis, death is a skeletal woman luring men to their fate. "This is where the femme fatale comes from. Those tropes have never left society."

They are not real

ReplyDelete